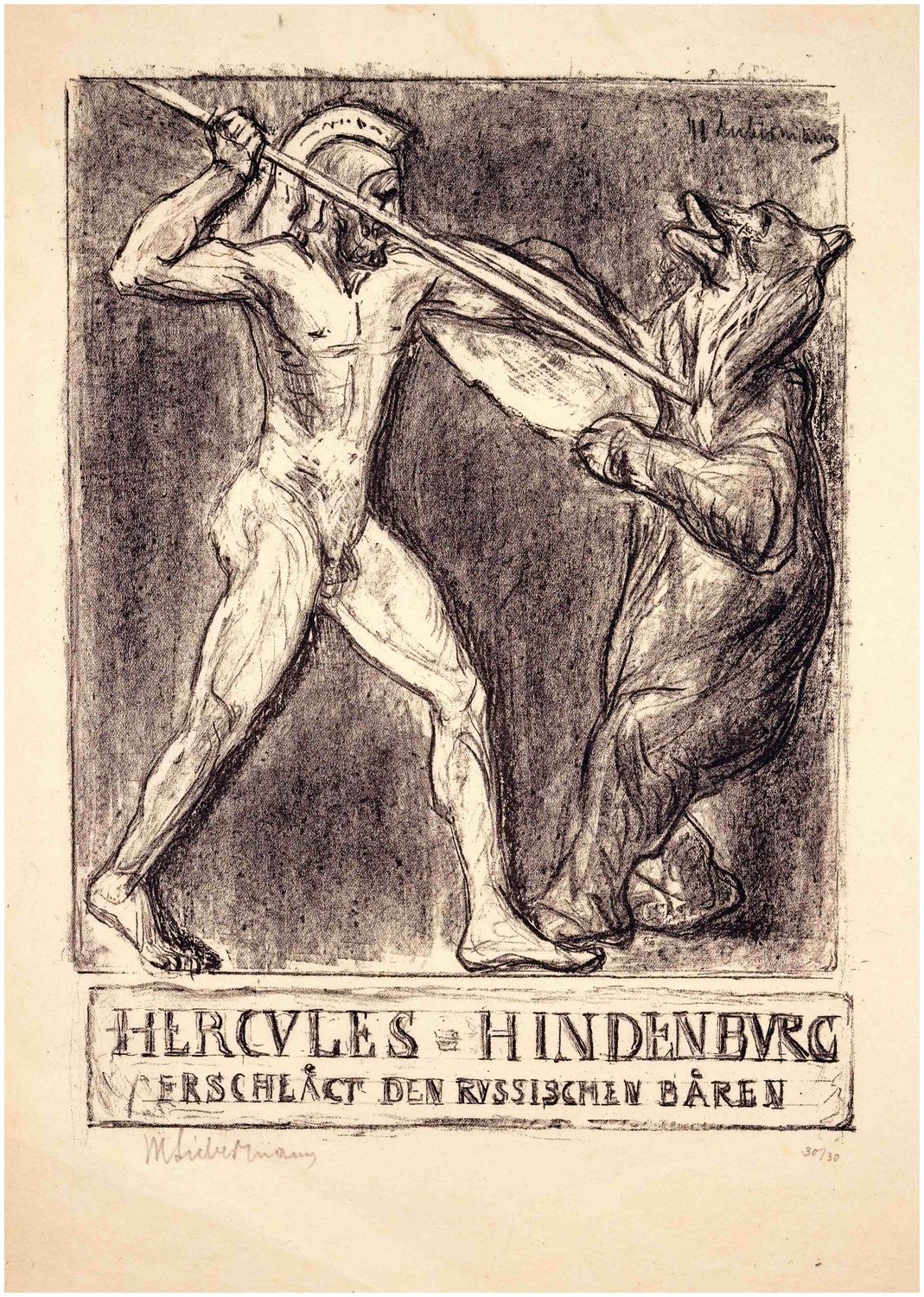

Liebermann, Max (1847–1935), Hercules – Hindenburg Slays the Russian Bear, 1914

Max Liebermann(1847 Berlin – 1935 ibid.), Hercules – Hindenburg Slays the Russian Bear , chalk lithograph on Japan paper, 32 cm x 23.5 cm (image), 42.5 cm x 30.5 cm (sheet), signed in the plate at top right and in pencil with „MLiebermann“ at bottom left, marked as copy no. 30/30 at bottom right.

- The upper margin has a minimal water stain, and both the upper and lower areas show light creases. Otherwise, the extremely rare print is in good condition.

- Classical Impressionism -

The lithograph Hercules – Hindenburg Slays the Russian Bear is an allegory of the Battle of Tannenberg and was created in the context of Max Liebermann’s collaboration with the magazine Kriegszeit, published by Paul Cassirer. The lithograph appeared in the September 1914 issue.

With wide strides, Hercules, depicted heroically nude, subdues the dark bear pushed to the edge of the image. Both figures cast slight shadows, making the background appear like a relief. This lends the scene the appearance of an ancient frieze, emphasizing a commemorative, monumental quality that is further reinforced by the use of antique capital lettering.

In this depiction, Liebermann draws on the neoclassical repertoire of Bertel Thorvaldsen, though he revives these adopted visual formulas with his characteristic fluid impressionist linework.

The lithograph, printed on Japan paper, signed by hand and published separately in a very limited edition of only thirty copies alongside its appearance in the magazine, is a testament to Liebermann’s artistic belief that his work marked the beginning of a new classical age.

About the artist

The young Liebermann, who pursued his artistic talent against the wishes of his father—who had wanted him to study chemistry—was employed by Carl Steffeck to assist with his monumental battle paintings. With Steffeck, Liebermann met his future patron Wilhelm von Bode. He then studied under Belgian history painter Ferdinand Pauwels at the art school in Weimar, where he delved into Rembrandt's print works, which would remain a key influence throughout his career. In 1871, Liebermann stayed in Düsseldorf, where he was drawn to the dark-toned realism of Mihály von Munkácsy. This was followed by travels to the Netherlands, where he studied the landscapes and figures of the Dutch masters he so admired. His first large-scale painting, The Goose Pluckers (1872), was shown in Hamburg and then Berlin, earning him the reputation of a "painter of the ugly." He then went to Paris and later Barbizon to study plein-air painting. Returning once again to Holland, Liebermann copied works by Frans Hals, which influenced his brushwork and brightened his color palette. Despite his growing alignment with French art and regular participation in the Paris Salon, Liebermann struggled to establish himself in the Parisian art scene.

In 1878, he traveled to Italy, where he connected with Franz von Lenbach and Munich painters, prompting him to move to Munich. There, his painting The Twelve-Year-Old Jesus in the Temple triggered an anti-Semitic backlash, forcing him to revise the controversial depiction of Jesus.

On another trip to the Netherlands, Liebermann was captivated by a scene of black-clad men sitting on benches in the sunlight in the garden of a retirement home. While painting this, he developed the characteristic "Liebermann sunspots" that would define his later work.

In 1884, Liebermann returned to Berlin and was admitted to the Verein Berliner Künstler (Berlin Artists’ Association), with the support of his later adversary Anton von Werner. Through the Bernstein family, he became acquainted with Max Klinger, Adolph von Menzel, Wilhelm Bode, Theodor Mommsen, Ernst Curtius, and Alfred Lichtwark, director of the Hamburg Kunsthalle and a key patron. In 1886, after an eight-year hiatus, Liebermann again exhibited at the Academy of Arts and was now celebrated by critics as a leading figure of modernism. Adolph von Menzel praised him as "the only one who paints people, not models." His works shown at the 1889 World's Fair brought him international success; he received an honorary medal and was inducted into the Société des Beaux-Arts.

In 1892, the premature closure of a major Edvard Munch exhibition—due to a vote by the Verein Berliner Künstler—caused an open rift between the academic-conservative faction led by Anton von Werner and the modernist faction championed by Liebermann. Liebermann joined the Vereinigung der XI (Association of Eleven), which would later give rise to the Berlin Secession. Despite this split, in 1897, on the occasion of his 50th birthday, Liebermann was honored with an entire hall at the Academy exhibition and awarded the Grand Gold Medal. With Werner’s support, he was admitted to the Academy and appointed professor. However, when a painting by Walter Leistikow was rejected from the 1898 Große Berliner Kunstausstellung (Great Berlin Art Exhibition), Leistikow called for the founding of an independent artists' group—the Secession—with Liebermann elected president. The Secession exhibitions, featuring artists from Worpswede as well as Arnold Böcklin, Hans Thoma, Max Slevogt, and Lovis Corinth, became international events, prompting Corinth and Slevogt to move to Berlin.

In 1903, Liebermann published The Imagination in Painting, criticizing academic art and arguing that the artist must find an interpretation of nature most suited to painterly means. This also set him apart from the rising Expressionists and foreshadowed future Secession conflicts. By this time, Liebermann had assumed Menzel’s social role in Berlin. In 1907, the Berlin Secession honored its president with a major birthday exhibition.

Since 1900, Liebermann increasingly focused on printmaking and standalone drawings. In 1908, 59 of his etchings were shown at the Secession’s Black and White exhibition. After rejecting 27 Expressionist works from the 1910 Secession show, Liebermann clashed with the younger avant-garde, led by Emil Nolde. This led to the formation of the Neue Secession under Max Pechstein, whose members included artists from Die Brücke and the Neue Künstlervereinigung München. In 1911, Liebermann stepped down as president but remained honorary president. Leadership passed to Lovis Corinth. After further internal disputes, Liebermann led the founding of the Freie Secession, which held exhibitions from 1914 to 1923.

In 1910, Liebermann had moved into his villa on Lake Wannsee, a recurring motif in his late work. At the outbreak of World War I, he contributed graphics to the magazine Kriegszeit, published by Paul Cassirer. He was among the 93 signatories of the nationalist appeal To the Civilized World, which denied Germany’s alleged war guilt with six emphatic "It is not true!" statements. Liebermann described his patriotic stance: “All my education I received here, I spent my whole life in this house that my parents already lived in. And in my heart, the German homeland lives on as an inviolable and immortal concept.”

For his 70th birthday in 1917, the Berlin Academy held a major retrospective of 200 of his paintings, and a dedicated Max Liebermann Room was opened in the National Gallery. In 1920, he became president of the Academy, marking the end of the Secession era. He inducted artists such as Max Pechstein, Karl Hofer, Heinrich Zille, Otto Dix, and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff. In 1927, for his 80th birthday, another major solo exhibition celebrated the artist now regarded as a classic. He was offered honorary citizenship, and President Paul von Hindenburg awarded him the Eagle Shield of the German Reich “as a token of gratitude owed to you by the German people,” while Interior Minister Walter von Keudell presented him with the Golden State Medal.

When the Nazis marched past his house at Pariser Platz on the day of their seizure of power, Liebermann reportedly said: “I couldn’t possibly eat as much as I would like to throw up.” He resigned from his official positions and retired to Wannsee, where he painted one final self-portrait in 1934. Max Liebermann died on February 8, 1935, in his home on Pariser Platz. His death mask was made by Arno Breker.

Selected Bibliography

Max Liebermann, Max: Die Phantasie in der Malerei – Schriften und Reden. Mit einem Geleitwort von Karl Hermann Roehricht und einem Nachwort von Günter Busch, Frankfurt am Main 1986.

Sigrid Achenbach: Die Druckgraphik Max Liebermanns, Heidelberg 1974.

Gustav Schiefler: Max Liebermann. Sein graphisches Werk. 1876 - 1923, San Francisco 1991.

Katrin Boskamp: Studien zum Frühwerk von Max Liebermann mit einem Verzeichnis der Gemälde und Ölstudien von 1866 bis 1889, Hildesheim 1994.

Matthias Eberle: Max Liebermann. Werkverzeichnis der Gemälde und Ölstudien, München 1995.